Book Excerpt: Introduction

Excerpted from Blindfold Chess: History, Psychology, Techniques, Champions, World Records, and Important Games, © 2009 Eliot Hearst and John Knott. By permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com

Visualize this scene. A chessmaster sits at an empty table with his back to 20 players, who are arranged in a rectangle behind him and have their own chessboards in front of them. He cannot see any of the 20 positions on his opponents’ boards. The boards are numbered consecutively from 1 to 20, in a counterclockwise manner starting from the master’s left side. All opponents have the Black pieces and therefore the master has the first move in every game.

He is taking on the 20 opponents at once and calls out his first move on each board in standard chess notation, going quickly around the rectangle from Board 1 to Board 20. The master is very swift in this first go-around because he decided long before the exhibition exactly what his first move was going to be on each board number, and he must have a planned system since he does not play the same first move on all boards.

Now that every one of the 20 players has heard what opening move the master played against him, and each opponent himself (or a referee, also known as a “teller”) has actually made the master’s initial move on his chessboard, the focus returns to Board 1. Here, the player must be ready with his response, which he makes on the board in front of him. Then the player or referee calls out the move to the exhibitor, who then calls out his second move on that board. The action immediately shifts to Board 2, where the player there must be ready with his first move, which the master then answers quickly with his second move. The play continues in this manner around the 20 boards, until play returns again to Board 1 where the opponent has to make his second move, which is called out to the master, who then calls out his third move.

Above: François-André Philidor playing blindfolded at Parsloe’s Chess Club in London in the 1780s. (Credit: Courtesy Edward Winter).

And so on, perhaps for many, many moves, until every game is finished by the master’s either checkmating his opponents on certain boards, forcing his opponents to give up (“resign”) on other boards because the position is hopeless, or drawing the game (when both the exhibitor and the player receive half a point). The only other alternative outcomes are that, heaven forbid, the master is checkmated or resigns a game to his opponent, or that an opponent has to leave and is either forfeited or another player is allowed to replace him and continue the game from the position already reached. Whether such unfinished games are scored as forfeits, or a player replacement is allowed, depends on rules set up beforehand. Most exhibitors will allow player replacement since there is no honor in winning a close game by forfeit.

Because the master is continually receiving and making moves on the other boards, each opponent has much more time to think than the master, but the sighted player must move as soon as the master “arrives” at his board. The exhibitor may in theory spend as much time as he likes before calling out his move. In practice, however, he will usually answer quite rapidly, for otherwise a 20 board display might last for days. Most games last on the average 20 to 30 minutes (that is, the total time devoted to that particular game, which would depend mainly on the exhibitor’s rate of play and the length of the game), so that 20 games might take more than 8 hours to complete. Obviously some exhibitors play much faster than others, but displays with more than 15 opponents are never over in the time it takes to play a game of tennis or baseball. They are long and grueling efforts, especially for the master because he cannot let his attention wander. Even though the games are “out of sight,” they can never really be “out of mind.”

Visualizing a blindfold chess exhibition is much easier to do than actually giving one. Many years ago, the master might have worn a blindfold over his eyes, but nowadays that would be regarded merely as a dramatic gesture. Instead, he will simply be located where he cannot see any of the games. In the recent movie The Luzhin Defence (2000), based on Vladimir Nabokov’s novel about an eccentric champion, the grandmaster (Luzhin) is shown giving a sightless display while wearing a blindfold—but this was only to let the audience know what is going on, without wasting words to describe it. In the novel on which the film was based (The Defense, 1964), Nabokov wrote that Luzhin found deep enjoyment in giving blindfold exhibitions:

One did not have to deal with visible, audible, palpable pieces whose quaint shape and wooden materiality always disturbed him and always seemed to him but the crude, mortal shell of exquisite, invisible chess forces. When playing blind he was able to sense these diverse forces in their original purity. He saw then neither the Knight’s carved mane nor the glossy heads of the Pawns— but he felt quite clearly that this or that imaginary square was occupied by a definite, concentrated force, so that he envisioned the movement of a piece as a discharge, a shock, a stroke of lightning—and the whole chess field quivered with tension, and over this tension he was sovereign, here gathering in and there releasing electric power [pages 91–92].

We will see later that this passage from Nabokov, who was an avid chess player, is not very far from what real blindfold champions might say (in a much less exotic way).

There are a variety of ways in which different exhibitions may stray from the scene visualized above. Sometimes the master is in a separate enclosed room or booth and hears and transmits moves by microphone, and sometimes he chooses not to have the White pieces on every board. There are no strict, official international rules governing blindfold play, probably because organizers consider it mainly a form of entertainment. The absence of rigid regulations often makes it difficult to compare the achievements of individual players. Various questions arise: Should the master be forbidden to write down anything, such as the names of the players or the openings at each board? What happens when an opponent, or the master, makes an illegal move? (In regular chess such a move has to be replaced, if possible, by a legal move of the same piece). Can and should the master take a break of a few hours or longer if he is tired? How can one compare the feat of playing 40 boards blindfolded against fairly weak opponents with the feat of playing against 30 strong adversaries? If the master offers draws that are accepted after a few moves in a good number of games, so that he can decrease the number of opponents quickly, how should his performance be compared to that of a master who fights every game to a finish?

Above: Alexander Alekhine (1892–1946) playing blindfold against 28 opponents in Paris in 1925, thus setting a new world record and surpassing the world record of 26 opponents he had set the year before. (Credit: Courtesy Edward Winter).

Since world records for blindfold chess are ordinarily judged by the chess public solely on the basis of the total number of opponents one has played, the lack of strict rules about the above and other questions makes it hard to decide which blindfold champions have achieved the greatest feats. We will have much to say about such details in this book. And because we include the most complete collection of games that our years of research could muster, for most world record–setting exhibitions the expert reader can judge the quality of the master’s play as well as that of his opposition.

Regardless of these possible variations in the particulars of different displays, many psychologists and informed members of the chess and other communities believe—in our view, justifiably—that the playing of more than 20 or 30 simultaneous blindfold games ranks among the most amazing achievements of human memory. Not only must the master recall the constantly changing positions in all the games, which tend to have an average length of 25 to 40 moves, but he must also find good moves. If he does not win at least 70 percent of the games, the display is not usually considered a success—unless the opposition is extremely strong.

Such well-known authorities as polymath Douglas Hofstadter in the field of artificial intelligence and experimental psychologist Endel Tulving in the field of cognitive neuroscience and human memory have told Hearst that, in their opinion, no other human memory feat can surpass the achievements of the best simultaneous blindfold champions. However, blindfold chess involves more than just memory. Among other things, it calls for a memory that is linked with understanding, expertise, imagery, calculation, and recognition of meaningful configurations or patterns.

On the basis of our research, we will try to isolate the skills and techniques that the blindfold player must possess to attain his feats. In other words, how does the blindfold champion do it?

As chess entertainment, blindfold chess ranks highly. Grandmaster Andrew Soltis declared that “it is the single most dramatic way to attract attention to chess.” Former world champion in regular chess Anatoly Karpov called blindfold chess an “entertaining spectacle.” So we are not going to be talking about some very esoteric form of chess, fascinating only to a select few people, but a version of the game that spectators love to watch. They can see the actual positions, now on large, computer-controlled wall boards.

Even though the point does not refer to multi-game simultaneous blindfold displays, it is relevant and perhaps surprising that some of the world’s top grandmasters have not even owned a real chess set when they were at their best. On a visit to José Capablanca’s home, Julius du Mont was astonished when he found that Capablanca did not possess a complete chess set and that for a game he had to use an assortment of household articles as improvised pieces. The only matching pieces were the two white rooks, which were represented by sugar lumps! In his book The Inner Game(1993, page 133), Dominic Lawson wrote that British world championship challenger Nigel Short never seemed to have a chess set in his rooms during his match with Kasparov in 1993. Short was “much happier discussing positions from the games ‘blindfolded,’ without the unnecessary tedium of actually moving the pieces. And besides, this way his hands were free to play the guitar.” In conventional tournament play Russian Grandmaster Peter Svidler walks around a great deal between moves, often analyzing his ongoing game in his head while walking. In 1997 he said: “I don’t have to look at the board. If you don’t know where the pieces stand, you’re not a chess-player.”

Svidler’s remark is not atypical for skilled chess players. Even in regular tournaments there are a number of grandmasters who occasionally cover their eyes, stare into space, or look at the ceiling while deciding on their next move. Many masters have said that sight of the actual pieces sometimes hinders their analysis, which reminds us of Nabokov’s hero implying that a piece itself is merely a crude representation of its intrinsic force. We will discover from reports of blindfold experts that the better they are, the less likely they are to visualize real pieces and squares and the more likely they are to describe their experience abstractly as involving interacting “lines of force” or as a clash between the potentialities of action embodied in characteristic features of a position.

Again, one thing is clear: Blindfold champions are not just memorizing moves; rather, they have the ability to grasp meaningful relationships among different aspects of a board situation. They “understand” what is important to direct their attention toward and what is less so. Obviously, such skills play a large role in regular chess, too.

Alexander Alekhine, the world champion in regular chess for most of the period between 1927 and his death in 1946, will turn out to be our clear choice for the best blindfold player of all time. He did not think that the quality of his play in multi-game simultaneous displays came close to approaching the skill level he demonstrated in regular games, an opinion with which other blindfold champions will almost all agree about their own play. (One obvious reason for this is that in regular, serious games a master has much more time to think about each move.) And Alekhine said that it was impossible to avoid a few errors of memory in blindfold events. Still, he included blindfold games in collections of his best games and some are real gems.

Most readers who may not know much about the existence of large-scale blindfold exhibitions have usually heard about or seen simultaneous displays where a player is not blindfolded but walks around all the assembled boards. There the master often takes on many more than 40 or 50 opponents, according to the same arrangement as in blindfold exhibitions—except of course that the master can see the actual position as he arrives at each board. No one has attempted more than 52 blindfold games at once, but the world record for number of adversaries in sighted simultaneous play is obviously much higher. It is not clear who holds this record, which is certainly in the hundreds or, according to some reports, even over 1,000. Miguel Najdorf of Argentina, who we will argue is the rightful holder of the world simultaneous blindfold record at 45 games, played in 1947, has met as many as 250 opponents at once in regular simultaneous play, which took him 11 hours to complete in 1950. (Playing the 45 blindfold games took him nearly 24 hours!) We did not delve into the accuracy of the numerous reports about world records for regular simultaneous play; our excuse is that we devoted years to research on blindfold displays and could not bring ourselves to do the same for regular exhibitions—which we do not find as challenging or fascinating.

Miguel Najdorf (1910–1997), who the authors argue is the rightful holder of the world simultaneous blindfold record at 45 games, played in 1947. (Credit: Courtesy Edward Winter.)

Standard, sighted simultaneous exhibitions are mainly tests of one’s physical fortitude, walking around for so many hours, whereas blindfold chess introduces much more than that. Although blindfold players can sit during their exhibitions and such lengthy efforts do require someone to be in good physical shape, the mental fatigue is much greater than in any regular simultaneous exhibition, where you do not have to worry much about memory or visualization problems since you can see each position as you arrive at a board.

Because of the effort and concentration required to play many simultaneous blindfold games, no one has seriously attempted to play more than 28 such games since 1960. Money prizes in regular tournaments have increased markedly during recent years, as have the sheer number of such events open to participation virtually every weekend in many countries—a spurt of professionalism and opportunity that many masters attribute to the unyielding financial demands of Bobby Fischer and the media interest created by his often eccentric behavior. Now it is much easier to make a decent living by playing regularly in standard tournaments, and writing about and teaching chess, than by scheduling tours like those arranged by such great blindfold players of the past as Blackburne, Zukertort, Pillsbury, Alekhine, and Koltanowski. However, two players have told us that they intend someday to play at least 30 blindfold games at once.

The main form of blindfold play today is in high-class tournaments where individual players compete one-on-one against each other. That is, they play under normal tournament conditions, but through the use of computer technology neither one of them can see the actual position. Sitting a few feet apart, the players type or “click” their moves onto a computer keyboard, and their own monitors merely display an empty diagram and the notation of their opponent’s last move. The annual tournament in Monaco, half blindfold and half regular chess, has attracted almost all the very best players in the world, because of the beautiful setting for the event, the generous prize money, the fact that the games are not internationally rated so one cannot suffer from a few bad losses, and the chance to play a different variety of chess from the usual.

But does the quality of play in these one-on-one blindfold games approach the quality of the games played with sight of the board in the same tournament? We will have more to say about this question later. The issue is worth examining for many reasons, not the least of which have been the boasts of many players that they can play one game blindfolded as well as they can play a regular game.

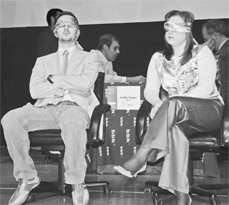

Though blindfold chess rarely involves actual blindfolds, Veselin Topalov and Judith Polgar are blindfolded here at the start of their six-game computerized blindfold match at Bilbao, Spain, in December 2006. Topalov won the match 3 1/2-2 1/2. After the first few moves they removed their blindfolds and used individual computers. (Credit: courtesy New in Chess.)

Noteworthy is the fact that many chess teachers and writers recommend practice at blindfold chess as a way of developing one’s regular chess skill. They also advise players to mentally “play over” complete games or games from diagrammed positions in magazines or newspapers with the remaining moves given in chess notation. Grandmaster Alexander Beliavsky, among others, has the habit of carefully analyzing a number of games every day without the sight of any chessboard. Techniques of these kinds were a part of the training procedures used in the Soviet Union for accelerating a promising youngster’s growth as a chess player, and today they have been adopted by many teachers in other countries.

Chess-in-the-schools programs in the United States have burgeoned and many secondary schools in different cities offer chess classes. (Some evidence suggests that these classes improve students’ overall grades, motivation to think critically, patience, concentration, self-confidence, and general interest in intellectual activities.) Hundreds of schools compete in national scholastic championships, which include many different age levels. A special program developed by Ruby Murray in Washington State involves a large number of visualization exercises. The children call it “bat chess” (blind as a bat). And available computer programs allow one to play blindfolded against a computer (see, for example, Robert Pawlak’s 2001 article on programs of this type).

These educational possibilities, as well as different forms of visualization training, have obvious application to other fields of human endeavor, which we will occasionally mention. We believe strongly that the topics, techniques, and skills to be discussed and evaluated here have implications for, and uses in, many fields outside chess; our view is that this volume is not a book that has utility and interest only for chess players and scholars like psychologists and historians. In his book The Great Mental Calculators (1983, page 105), Steven B. Smith mentions that learning how to calculate quickly engendered an interest in abstract thought in the Samoan general population. There, the introduction of mental multiplication led to an absolute craze for arithmetic calculations. “They laid aside their weapons and were to be seen going about armed with slate and pencil, setting sums and problems to one another and to European visitors.” If only blindfold chess could create such a furor!

We will also have to confront the issue of whether playing multi-game simultaneous displays, or engaging in excessive blindfold play of any kind, is dangerous to one’s health, as some medical and other experts have proposed over the past two or three centuries. Stefan Zweig’s The Royal Game (1944) tells the story of a Nazi prisoner’s success in avoiding insanity while in long solitary and barren confinement. He succeeded by luckily managing to steal a book of chess games without diagrams and playing over games from that book endlessly in his head—until eventually he grew tired of that activity and started to play games endlessly against himself. After his eventual release from prison, he finds himself on a ship which is also transporting the world chess champion to Buenos Aires, and he is talked into contesting a game with him. We will not reveal the story’s ending, but blindfold chess was not just a salvation for him but also a danger.

Although we have tried to make this book as interesting and absorbing as possible, perhaps we can still afford to conclude this introduction with a description of an incident reported in the British Chess Magazine in 1891 that might otherwise lead to a different conclusion. Charles Tomlinson wrote about when Robert Brien (editor of the Chess Player’s Chronicle) played a single blindfold game against three consulting amateurs. “Brien sat apart and spread a handkerchief over his head, to prevent distraction from surrounding objects. The game had proceeded many moves when, Brien being a very long time in moving, one of the antagonists called out to him, but getting no response, went up to him, and raised the handkerchief, when the editor was found to be fast asleep.”